Lukasz Czarnecki, Ph.D.

lukasz@comunidad.unam.mx

https://lukczar.weebly.com/

This short contribution aims to analyze schooling, human development, and income in three countries: Mexico, South Africa, and Vietnam. There is a common similarity for them that includes the economic market liberalization started from the 1990s. The post-Washington Consensus in Latin America, the post-Äổi má»›i period in Vietnam, and post-apartheid era in South Africa opened the possibility of improvement of schooling in terms of human development and better income conditions.

However, there is at least one difference between them. I follow the division made by Branco Milanovic (2019) who divided capitalism into liberal meritocratic on the one hand, and political on the other. Mexico and South Africa are liberal meritocratic capitalistic countries, but Vietnam is a country where political capitalism was implemented as a “product of communist revolutions conducted in societies that were colonized or de facto colonized†(Milanovic, 2019: 67).

The policy based on the neoliberal approach created social practices that make up a socio-political-economic and cultural totality not without contradictions (Rivero Bottero, 2013). The education based on the meritocratic and human capital approach is promoted in South Africa and Mexico. The historical boundaries created during the colonial past history in the post-appartheid era (Mathebula, 2018) in South Africa are supposed to be over; in Mexico there was implemented the policy based on free competition according to certain standards, in the same way that competes any other good or service offered in the market (Mercado Yebra et al., 2016). In addition, according to Milanovic, regarding the education in liberal meritocratic countries:

“The high cost of education, combined with the actual or perceived educational quality of certain high-status schools, fulfills two functions: it makes it impossible for others to compete with top wealth-holders, who monopolize the top end of education, and it sends a strong signal that those who have studied at such schools are not only from rich families but must be intellectually superior†(Milanovic, 2019: 60).

I will conduct the data analysis in two-time laps, in 2000 and 2017, followed by the model regression to explain schooling in three countries wishing to compare liberal and political capitalistic countries.

Descriptive analysis

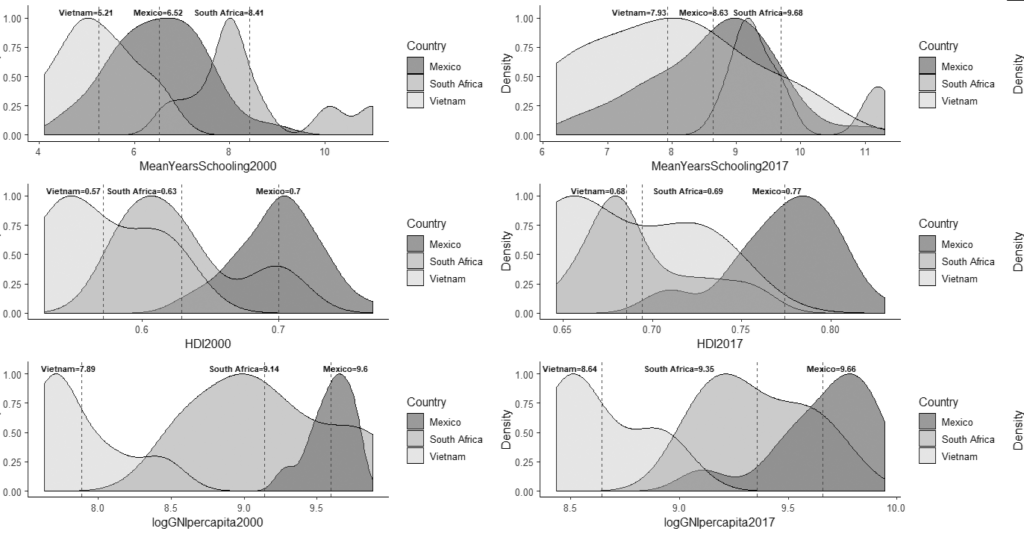

Figure 1 shows the means years of schooling, HDI and GNI per capita. The schooling for South Africa is the highest and it scored 8.41, comparing to Vietnam, 5.2, and Mexico, 6.52 for 2000. This variable increased to 9.68 for South Africa, 8.63 for Mexico and 7.93 for Vietnam in 2017. The highest increase during observed time laps was observed in Vietnam.

As far as HDI is concerned, it shows that Mexico had the highest score (0.7), comparing with South Africa (0.63) and Vietnam (0.57) in 2000. The results after almost two decades were as follows: 0.77, 0.69 and 0.68 for Mexico, South Africa and Vietnam respectively. The same as previous graph, the highest increase during observed time laps was observed for Vietnam, the country decreased the gap of HDI comparing two other countries.

Finally, in case of GNI per capita we observed the highest increase for Vietnam; almost without change for Mexico and slightly improvement in South Africa.

We observe that during the 17 years between two-time laps, the variable of HDI and GNI per capita do not increased as much as we would expect. They are almost the same, however in case of Vietnam there is a substantial growth. The years of schooling increased significantly for all three countries, however, the Vietnamese case registered the greatest growth, from 5.21 to 7.93.

Figure 1. Density plots for years of schooling, HDI, and GNI per capita in Mexico, South Africa and Vietnam, 2000 and 2017

Source: own extrapolation based on official census data for Mexico, South Africa and Vietnam in 2000 and 2017.

Linear regression model

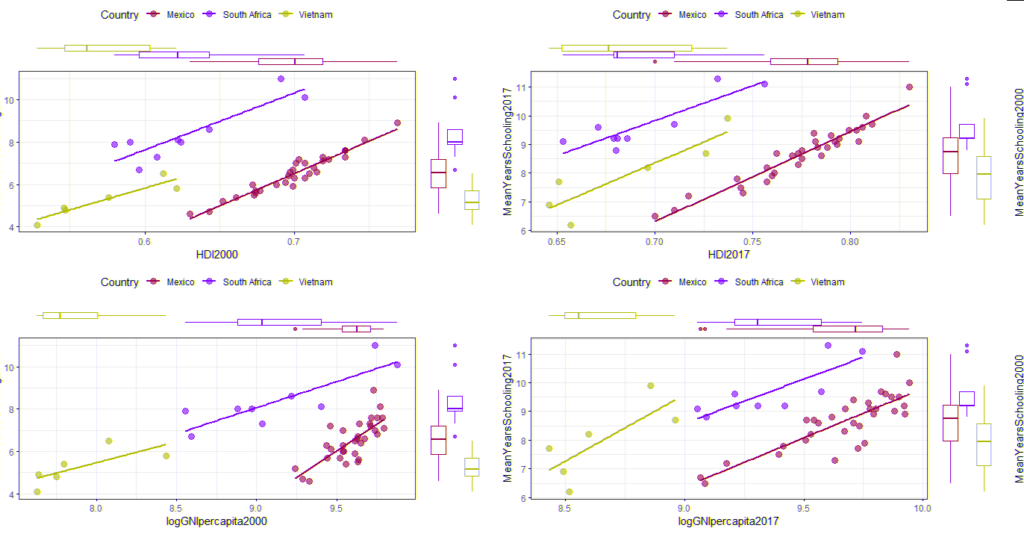

I developed two models to estimate years of schooling (YoS_est), having previously data on observed years of schooling in three countries in 2000 and 2017. I proceed with analysis of two models that evaluate relation between schooling and Human Development Index and GNI per capita. The first one consists of estimating years of schooling in terms of HDI (Model 1); the second one, years of schooling in terms GNI per capita (Model 2). The models implies two similar positive slopes with different intercepts.

Model 1

β0 + β1*+ β2*CodeCountry + ε

β0 + β1*+ β2*CodeCountry + ε

Model 2

β0 + β1*+ β2* CodeCountry + ε

β0 + β1*+ β2* CodeCountry + ε

We observed that during 2000-2017, HDI increased for the countries, however, the highest growth was for Vietnam. Despite the highest level of HDI for Mexico, it is still South Africa that has the highest score for years of schooling. In Mexico there were implemented social programs destinated to improvement of education such as Progresa Oportunidades in 2002, then Prospera in 2014, so one might have expected that the years of schooling would increase, but it was not the case.

Regarding LRM for schooling in terms of GNI per capita in 2000 and 2017, we observed that Mexico increased GNI per capita but it didn’t follow the increase in terms years of schooling. For Vietnam, the increase of GNI per capita meant the significant positive change for schooling. Meantime in South Africa, we observed the almost the same values in terms of GNI per capita and incensement in years of schooling.

Figure 2. LRM for schooling in terms of HDI and GNI per capita 2000 and 2017

Source: own extrapolation based on official census data for Mexico, SA and Vietnam in 2000 y 2017.

Conclusion

We observe that years of schooling is positively correlated in three countries in terms of both GNI per capita and HDI. However, between 2000 and 2017 it was Vietnam who registered the most significant progress. Liberal capitalistic countries experienced less progress due to growing gaps between poor and rich, meritocratic approach that facilitates social mobility mostly for the last, and concentration of the capital in the hands of few. Instead, more egalitarian approach is being implemented in the countries such as China and Vietnam.

Reference:

Mathebula, Thokozani. 2018. Human rights and neo-liberal education in post-apartheid South Africa, Journal of Education, Issue 71, doi: 10.17159/2520-9868/i71a06

Mercado Yebra, JoaquÃn, Luz Marina Ibarra Uribe, and Carmen Leticia Borrayo RodrÃguez. 2016. PolÃtica educativa en el México neoliberal, gasto público y oferta educativa, Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias, 3(6), 169-185.

Milanovic, Branco. 2019. Capitalism, Alone The Future of the System That Rules the World. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Rivero Bottero, Raquel. 2013. Educación y PedagogÃa en el marco del neoliberalismo y la globalización, Perfiles educativos, vol.35 no.142, 149-166.

Official census data, National Institute for Geography and Statistics, Mexico, 2000 and 2017.

Official census data, South Africa, 2000 and 2017.

Official census data, Statistical Office of Vietnam, 2000 and 2017.